LINKS

Web hyperlinks to non USD1812 sites are not the responsibility of the NSUSD1812, the state societies, or individual USD1812 chapters.

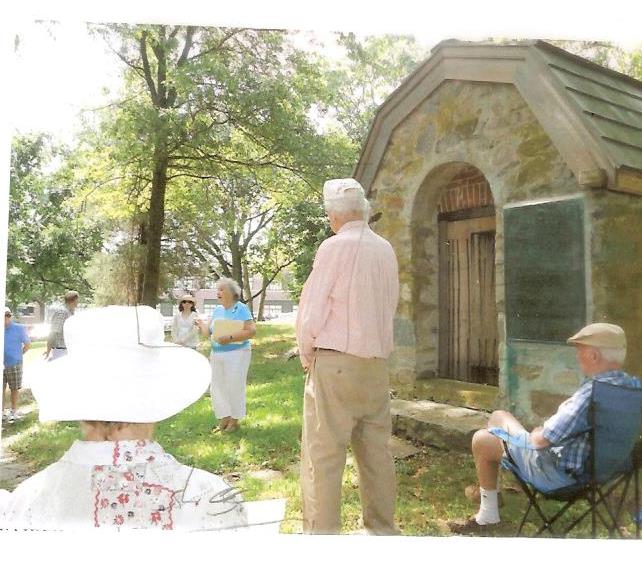

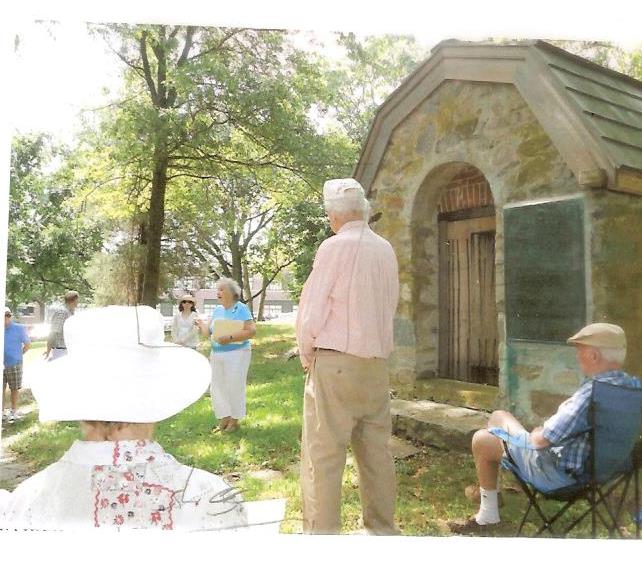

The Powder House in Fairfield Connecticut

The powder house still stands as a reminder of what early Fairfield residents did to defend the town, and it is the only remaining powder house that was built in Connecticut for the War of 1812.

SOCIETY NEWS CLICK HERE

SOCIETY NEWS CLICK HERE

For Selected Facts About Connecticut please SEE

website New London Historical Society worth a LOOK

Stonington Historical Marker Click Here

Stonington Battle Flag Click Here

History Stonington Flag Click Here

Project Gutenberg History Defense of Stonington

Click Here

For Trumbull, J. Hammond. The Defence of Stonington (Connecticut): Against a British Squadron, August 9th to 12th, 1814. Hartford, CT, 1864 This is a detailed account which utilizes primary documents and benefits from the author having been able to interview some of the participants. Try this Link to Begin

Canadian researchers find HMS Terror, British ship that attacked Stonington in War of 1812 Click Here

NARRATIVE STONINGTON

Stonington - For the past 202 years, the Battle of Stonington never has been far from the minds of borough residents.

The two large cannons used to repel British Navy forces during four days in August 1814 sit in Cannon Square, their muzzles pointed south toward Stonington Point. Several of the British shells that tore through village homes and set them ablaze now sit atop small granite pedestals in front of a home on Main Street and in front of the Stonington Free Library.

Artifacts from the battle, such as British cannonballs that lodged in the walls of homes and the muster roll of defenders, are displayed in the Old Lighthouse Museum. The most prized artifact of them all, the 16-stars-and-stripes flag that the defenders flew during the battle, is kept in a climate-controlled room at the Stonington Historical Society after being displayed for years in the bank next to Cannon Square.

Those who stroll along the public walkway at the southern end of Stonington Commons may see a bronze plaque affixed to the side of the former mill complex that marks the spot of the small fort used in the battle. A granite monument at Stonington Point marks the spot where villagers moved a cannon to fire 18-pound balls on the four British ships.

While the battle was not strategically important, from an emotional and psychological standpoint it was vital, according to local author James Tertius deKay, author of "The Battle of Stonington: Torpedoes, Submarines and Rockets in the War of 1812."

"America at the time was having trouble with the war. Things were not going well," he said. "But suddenly this tiny little town of Stonington was victorious and sent the British Navy away with its tail between its legs. For a couple or three weeks, Stonington was the biggest news in America."

What makes the story even bigger is that this small group of defenders repelled a force led by famed Capt. Thomas Hardy, who was Adm. Horatio Nelson's flag captain at all of his great naval victories.

The Stonington Historical Society is the caretaker of the Stonington Battle Flag, shown above during its last public viewing in 2009. The flag was flown by the defenders of Stonington in 1814 while the village was under attack by the British. It will be on display as part of an exhibit at the Lyman Allyn Art Museum in New London starting July 6.

DeKay said that Hardy and the British had made a mistake in underestimating the tenacity of the people of Stonington.

In 1775, just before the start of the Revolutionary War, the British ship HMS Rose attacked Stonington in search of food. Residents refused to let crew members land. They pulled out two cannons and fired on the Rose, forcing it to leave. The residents then celebrated the anniversary of the event over the coming years.

"Stonington was very proud of the fact they fought off the British in 1775. And when the British came back in 1814 to do the same thing, they wouldn't allow it either," deKay said.

The British did not know that the residents still had those two cannons hidden away in a shed near what is now the Stonington Free Library. If needed, they could be pulled by horse or oxen down to the small fort, which actually was a 4-foot-high semi-circle that protected the men firing the cannon.

"You'd probably pass by it without noticing it, but it did protect the harbor," deKay said.

Those cannons, as well as a smaller one, eventually would inflict a great deal of damage on the British ships.

Uniform coat of injured militia member John Miner, who fought at the Battle of Stonington.

Also working in the defenders' favor was Jeremiah Holmes, who had been forced into service by the Royal Navy for three years before he escaped. While with the British, he became an expert cannoneer.

"So now he was given the chance to attack the very Navy that had pressed him into service, and he was delighted by it," deKay said.

Hardy had been given orders to attack communities along the East Coast as a way to turn the Americans' attention back home from Canada, which the British feared the Americans would take. For various reasons, Hardy ruled out other nearby towns such as New London, Mystic, Saybrook and Sag Harbor, N.Y., and so by default, as deKay writes in his book, Stonington became the target.

Stonington decides to fight

On Aug. 9, 1814, at about 3 p.m., four British ships came into view from Fishers Island Sound, stopping off Stonington Point. By 5 p.m. Hardy had sent a written message, which was exchanged between two rowboats offshore, that residents had one hour to leave as he did not want to "destroy the unoffending inhabitants residing in the Town of Stonington."

When the message was read to the crowd onshore, the residents agreed they would fight, and the British rowboat carried the message back to Hardy.

War of 1812 militia officer's coat from the Stanton-Davis Homestead Museum.

At 8 p.m., the bomb ship Terror began firing 130-pound incendiary shells on the village. It also fired rockets and cannonballs, the latter of which tore through wooden structures. Over the next three days, the Americans fired the two cannons and did much damage to the brig Dispatch, which was about a quarter mile offshore. Another of the ships, the frigate Pactolus, got stuck in shallow water off Sandy Point and had to unload cannonballs and shot in order to float free. Residents later salvaged the items and sold them in New York City.

The largest of the warships, the 74-gun Ramillies, remained two miles offshore, out of range of the American cannons, deKay said.

The two sides intermittently fired back and forth with periods of heavy bombardment by the British.

Two British sailors were killed and many more were wounded. One defender died several weeks later from complications from an injury he suffered in the battle.

At one point, the cannons were moved from the fort to Stonington Point, where they could fire at British Marines trying to land on the east side of the borough.

The shells from the Terror, which spewed a trail of fire and sparks as they arced over the borough, started fires that were extinguished quickly by fire crews. While about half the 120 structures in the borough were hit, only about 15 sustained serious damage. None was destroyed.

This Congreve rocket was among those fired by the British at the defenders of Stonington during the War of 1812.

On the morning of Aug. 13, the British ships headed off into Fishers Island Sound.

"The British definitely bit off more than they could chew," deKay said.

He described Hardy as a classy commander who did not want to leave a legacy of having destroyed a tiny American town and its group of brave defenders.

"That's why he was looking for a way out without being embarrassed," deKay said, adding that because of Hardy's stellar reputation, none of his superiors questioned him about the Stonington incident.

In 1840, the U.S. government decided to take the two cannons away. The town was up in arms and refused to relinquish them.

A parade in Stonington in 1914 commemorated the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Stonington. Here, a float carries the flag that flew during the battle.

"They wouldn't allow it, just like they wouldn't allow the British to push them around," deKay said.

J.WOJTAS@THEDAY.COM

2 Research Link: How to Find Your 1812 Ancestor

Click Here

CONNECTICUT HEROINES

Anna Bailey

At the time of the burning of New London, in Connecticut, a detachment of the army of the traitor Arnold was directed to attack Fort Griswold, at Groton, on the opposite side of the river. This fort was little more than a rude embankment of earth, thrown up as a breast-work for the handful of troops it surrounded, with a strong log-house in the centre. The garrison defending it, under the command of the brave Colonel Ledyard, was far inferior to the force of the assailants; but the gallant spirits of the commander and his men could not brook the thought of retreat before a marauding enemy, without an effort at resistance. They refused to yield, and stood their ground, till, overwhelmed by numbers, after a fierce and bloody encounter, hand to hand, with the foe, it was found to be impossible to maintain the post. No mercy was shown by the conquerors - the noble Ledyard was slain in the act of surrender, with the sword he had placed in the hand of the commander of the assailants - and after an indiscriminate butchery, such of the prisoners as showed signs of life, were thrown into a cart, which heaped with mangled bodies, were started down a steep and rugged hill towards the river.

The course of the cart being interrupted by stones and logs, the victims were not precipitated into the water; and, after the enemy had been driven off by the roused inhabitants of the country, friends came to the aid of the wounded, and several lives were preserved. Their sufferings before relief could be obtained were indescribable. Thirty-five men, covered with wounds and blood, trembling with cold, and parched with thirst, lay all night upon the bare floor, almost hopeless of succor, and looking to death as a deliverance from intolerable anguish. With the first ray of morning came a ministering angel to their aid - one who bore a name imperishably connected with the event - Miss Fanny Ledyard, a near relative of the commander who had been so barbarously murdered. She brought warm chocolate, wine, and other refreshments; and while Dr. Downer of Preston was dressing their wounds, she went from one to another, administering her cordials and breathing into their ears gentle words of sympathy and encouragement. In these labors of kindness she was assisted by another relative of the lamented Colonel Ledyard - Mrs. John Ledyard -who had also brought her household stores to refresh the sufferers, and lavished on them the most soothing personal attentions. The soldiers who recovered from their wounds were accustomed, to the day of their death, to speak of these ladies in terms of fervent gratitude and praise.

The morning after the massacre at Fort Griswold, a young woman, now Mrs. Anna Bailey, left her home, three miles distant, and came in search of her uncle, who had joined the volunteers on the first alarm of invasion, and was known to have been engaged in the disastrous conflict. He was among those wounded unto death. His niece found him in a house near the scene of slaughter, where he had shared the attention bestowed on the rest. His wounds had been dressed, but it was evident that he could bear no further removal, and that life was fast departing. Still perfect consciousness remained, and with dying energy he entreated that he might once more behold his wife and child.

Such a request was sacred to the affectionate and sympathizing girl. She lost no time in hastening home, where she caught and saddled the horse used by the family, placed upon the animal the delicate wife, whose strength could not have accomplished so long a walk; and taking the child herself, bore it in her arms the whole distance, and presented it to receive the blessing of its expiring father.

With pictures of cruelty like the scene at Groton fresh in her recollection, it is not surprising that Mrs. Bailey, during the subsequent years of her life, has been noted for bitterness of feeling towards the ancient enemies of her country. She was emphatically a daughter of the Revolution, and in those times of trial was nourished the ardent love of her native land for which she has ever been distinguished, and the energy and resolution which in later days prompted the patriotic act that has made her name so celebrated as "the heroine of Groton." This act was performed in the last war with Great Britain. On the 13th July, 1813, a British squadron appearing off New London harbor, an attack, evidently the enemy's object, was momentarily expected. The most intense excitement prevailed among the crowds assembled on both sides of the river, and the ancient fort was again manned for a desperate defence. In the midst of the preparations for resistance, it was discovered that there was a want of flannel to make the cartridges. There being no time to cross the ferry to New London, Mrs. Bailey proposed appealing to the people living in the neighborhood, and went herself from house to house to make the collections, and took even a garment from her own person to contribute to the stock. A graphic account of this incident, and of "Mother Bailey," appeared in the Democratic Review for January, 1847. But as a piece of historical justice, it is due to this heroine to state that she denies having used the coarse and profane expression there attributed to her. The highly intelligent lady residing in New London, who received the particulars I have mentioned from Mrs. Bailey's own lips, also says that she has never claimed the credit of being among those who ministered to the wants of the wounded, after the massacre at Fort Griswold. This characteristic instance of enthusiasm in the cause of her country, with the impression her remarkable character has produced, has acquired for her a degree of popularity, which brings many curious visitors, from time to time, to see and converse with the heroine of whom they have heard so much, and to look at her museum of Revolutionary relics.

Her maiden name was Anna Warner, and she married Captain Elijah Bailey, of Groton. She is still living, in her eighty-ninth year, in the possession of her mental faculties, able to describe the scenes of hardship and peril in which she shared in the nation's infancy, and still glowing with the ardent feelings of love to America and hatred to America's foes, which have given a coloring to her life.

For Source of Article Click HERE

SOCIETY NEWS CLICK

SOCIETY NEWS CLICK